My mother’s death anniversary was this week, Edna Lewis’s birthday is today, and this full, pink moon in Libra, with its ravishing daytime waxing, has been serving me powerful reflections and insights. Cake has been needed.

I finally watched Finding Edna Lewis, Deb Freeman’s thoughtful PBS documentary about the iconic chef. I’d argue Lewis is this country’s most important and influential chef. As the documentary description reminds us, Lewis introduced Americans to seasonal, Southern cooking through the lens of the Black Virginia community that raised her. Deb Freeman follows Lewis’s bio-geographical path in the hopes of shedding more light on the professional trajectory of a chef who should be a household name. I loved following along from my couch as Freeman took us from Virginia to Cafe Nicholson in late ‘40s New York, where Lewis was partner and chef feeding the bohemian literati, to Middleton Place in Charleston, where as executive chef, Lewis boarded in a converted rice mill where enslaved African and African Americans processed grain a few short generations before, and back to New York’s storied Gage & Tollner chophouse, where again in the executive role, Lewis brought the clarity of an elegant vision to life.

Anyone who wants to research Lewis’s life and work has to confront her sparse historical documentation. Her thin archival record underscores for me, the ways the foundational systems that structure this country continue to rely on Black women’s labor as central but are constitutionally unable to acknowledge it (pun intended). Part of why Lewis’s power and presence continues to grow is she has shown us another way.

Freeman’s documentary expertly unfolds, scene by scene, kitchen by kitchen, by each dish and conversation, the Lewisian path she wants us to journey with her. It’s important to understand the way Lewis’s presence and embodied knowledge challenged the institutions through which she traveled, and the ways her presence brought into relief the limitations, prejudices, blind spots and assumptions these institutions didn’t even know they held. But what Freeman’s documentary reminded me of with each extraordinary Black woman interviewed, was what has been true from the earliest of our days on this land, what has been proven in what we carry forward, and what is important to remember in this particular politico-historical moment: we are the institution, we are the archive. Our dishes, our kitchen-centered care, our bodies, our memory, our respect and labor and craft, our strong, supple, subtle, connected, collective body is where we will (always) find Edna Lewis.

Freeman interviewed such bright stars in Lewis’s constellation: Leah Branch, Lewis’s niece Nina Williams-Mbengue, Adrienne Cheatham, Mashama Bailey, Amethyst Ganaway, and Nicole Taylor! I’m thankful there’s room for the rest of us in this Black-as-night sky. Lewis’s wisdom is amplified through our words, kitchens, and gardens everywhere.

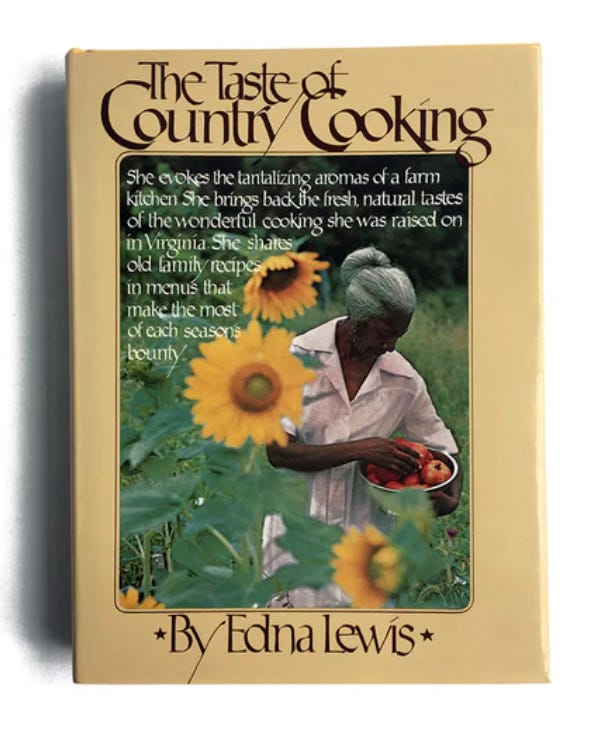

I had found Edna Lewis in my early twenties in the shape of a vintage copy of The Taste of Country Cooking tucked away on a shelf in the kind of New Orleans used bookstore I have always wanted to live in. An abiding love of Spoonbread and Strawberry Wine was inherited from my mother and this cookbook seemed akin in some way so it came home with me only to be tucked away on my own shelves. Edna Lewis then found me in my early thirties. I was in grad school at NYU, studying Black jazz women who were in many ways Lewis’s musical counterparts: brilliant, foundational, politically-informed, systemically overlooked and under-documented. Maybe because I missed my mom who was all the way back home in Georgia, maybe because in the Park Slope apartment I shared with my then partner, I felt like I was for the first time, making a kind of home of my own, maybe because I finally had people to cook for, but I devoured that tattered copy of Taste. It sparked a world of connections that helped me make sense of my Self-in-the-world. It put words and recipes to dreams and ideas and continues to do so.

I have written elsewhere about the kitchen-centered care my mother showered on my brother father, and I and friends and family. I know it was one of the ways she wove and maintained community. They originated from a place of love, curiosity, and talent but I know that the way her efforts in the kitchen were often pressed by the demands of working wifedom had to be exhausting. I was a sensitive kid and learned to read the currents of resentment and resistance that simmered under the casseroles and cobblers like chafing dishes. For me, Taste went far in unshackling kitchen-centered care work from domestic role compliance and dutiful performance and, throwing the doors of the kitchen wide, invited in ways to creatively participate in and celebrate the season and cycles of one’s (own) place.

My evolving understanding and joyful practice of sustainable, seasonal, soil-to-table cooking and baking starts with Edna Lewis.

My reverence for celebration and grieving as sites of practice involving food and table, and gathering as abundance starts with Edna Lewis.

My experience of my cooking/baking/eating self as always amplifying my body as powerful and porous but sovereign and as totally woven into the fabric of my placetime starts with Edna Lewis.

My insistence in my work–even as I continue to figure out what forms it should take–on the inseparability of season, cycle, and place and the importance of food as a way of opening up to big and multi-dimensional but subtle and ephemeral emotional and sensorial experiences? Lewis.

And so forth.

Just now, I am rereading Taste in parallel with Kōhei Saitō’s Degrowth Manifesto, Slow Down. I didn’t plan to, but I interrupted the already in-progress Saitō with the Lewis in advance of her birthday and now I’m going back and forth chapter by chapter. It didn’t take long to feel resonances between the rhythms and ethos of Lewis’s Freetown and the “radical abundance” of the cyclical, steady-state economic system of social ownership described in Slow Down as degrowth communism.

At the end of his life, Marx apparently had been in deep ethnographic study of links between strands of ecological thought and ancient Germanic communes. Saitō pulls together threads of research and thought that Marx himself did not have time to codify before he died. Threads that underscore the fact that 1) true sustainability and social equality are always already interlinked and 2) so-called “history” does not in fact move along a straight line of progress and endless growth fueled by capitalism but is instead always already multilinear (and I would add multidimensional). Edna Lewis knew all this and her people knew it through lived experience long before. This is why when writing about her chocolate cake I ended the piece with the statement that baking it reminds me that “solutions can be as much about remembering as innovating.” Capitalism straight lines and straitjackets our thinking towards progressive development and growth. But we can pick and choose what we want to carry forward. We can go back and get what we forgot. We can pull the meaning of key terms and concepts back in alignment with our own lives.

Saitō quotes Marx in Slow Down: “when people are liberated from the domination of capital and regain their ability to labor freely, the nature of wealth itself transforms [italics my own] (2024, p. 124).” The formerly enslaved and their descendants who built Freetown understood this through lived experience and made choices about the structure of their community that would increase the chances that the reciprocal needs of its people, its critters and its land would be met. They wrested the meaning of wealth back to something true, equitable and sustainable.

The part of Lewis’s archive that tugs at my curiosity the most right now is that early period in New York. I read she was married to a “radical member of the Communist party (Clark, 2018, p. 169) and that she worked for the Daily Worker. What was the nature of that work and what was the level of her interest and involvement in the Party? Did she see then as I do now, the resonances between Freetown’s practics and communism’s (always imperfectly manifested) potentials? Did she understand the interracial coalitions of communist New York in the 1940s as a viable path for racial justice? How did her travels within this political milieu shape her outlook, bearing, and understanding of her own experience going forward? I wonder, I wonder, I wonder. And I bake. And I dream–towards a present and future that I want to live in and want for others. It is easy–especially as Ms. Lewis’s celebrity as an American chef grows and glosses over the subtle embodied import of her work–to sink into a kind of “ nostalgic call to ‘return to the village’ but what if closer attention reveals that instead of a return to the past, Lewis’s work offers clues for how to reimagine (and re-member) the village as a way of “construct[ing] a whole new future” (Saitō, p. 123)?

There’s a moment towards the end of Finding Edna Lewis, that I love. Leni Sorensen, farmer, chef and keeper of kitchen ways sums up the cultural, geographical and historical specificity of Lewis’s oeuvre: “In this little place, for this little time, we had this…and it was beautiful.” Everyone’s thoughtful pause at the table seems to say “and that’s more than beautiful enough.” What if though, as Lily Kelting offers in her brilliant essay Edna Lewis and the Melancholia of Country Cooking, “Lewis’s cookbooks themselves hold the key to an ephemeral, sensory paradigm that might demonstrate the knowledge and cultural value of Lewis’s work outside a dominant paradigm.” (Kelting, 2018, p. 150)?

I wonder. I wonder. I wonder.

I feel closest to my mom in the kitchen (or in the aisles at Marshall’s). I wanted to bake something nice to honor her and because I’ve been busy (and because I had just watched Deb Freeman and Lewis’s niece Nina Williams-Mbengue make it on the show and it looked delicious), Lewis’s Busy Day Cake seemed appropriate. The cake’s straightforward approach was comforting (unlike her coconut cake) and it came together easily from ingredients already in my pantry. It was fragrant with vanilla and freshly grated nutmeg. It was tender, golden and completely unadorned. It was a full moon on the plate. Knowing what we know about Ms. Lewis, it makes sense that the cake seems designed to soak up the season’s fruit–preserved or fresh. I subbed in frozen blueberries for the blackberries and glugs of maple syrup for the sugar in my compote and added a spoonful of over-whipped cream to the side of my plate. Perfection. I’ll eat this cake in late summer with cantaloupe splashed with orange flower water. In fall with pears poached in warm aromatics and toasted for weekend breakfast with strong coffee and my own marmalade come winter. Maybe, as I sometimes do if I sense her hanging around, I’ll set a plate out for my mom.

***

Who are your heroes? Whose constellations are you proud to be a part of? How do they inspire your dreaming towards a world you want to live in and want for others?

Clark, P., 2018. Looking for Edna in S. Franklin (ed) Edna Lewis: At the Table with an American Original, (pp 156-169). University of North Carolina Press

Saitō, K., 2024. Slow Down: The Degrowth Manifesto. Astra House.