My heart dipped, just for a second, when, after asking my niece what kind of cake she wanted for her graduation she texted “ I think just a strawberry cake would be good.” You..think? Just a strawberry cake? The casual delivery and implied ease of the task–as though she thought she’d keep things simple for my sake–stung a bit too. I’m not sure what she was envisioning, but I was remembering my past attempts at fresh strawberry cakes. Pains in the ass, each time. An interesting and delicious scratch strawberry cake is not particularly straightforward or easy to pull off. This is a cake with logistical and technical challenges. For one, the season for lovely strawberries is fleeting and was fast coming to a close here in Georgia. A cake made with life-force-sucking grocery store mutants would hardly be worth the effort. Then, the texture of this ultimate springtime cake should be airy and light, like a breeze against your cheek in late May, an achievement I’ve found impossible to balance with intensity of flavor. The strawberry pulp threatens to reduce the crumb to a pudding. Finally, let’s be real, once we acknowledge the little miracles they are, even the lovelies, can sometimes veer toward a cotton candy sweetness that cloys without balancing elements.

Given the gentle baking grudges I hold against them (always projections of my own limitations), it’s a touch ironic that my favorite of Kimmerer’s essays in Sweetgrass is the one on strawberries. Unlike my strawberry cakes, this essay is technical perfection and one I return to again and again. My fondness is due at least in part because my father, like Kimmerer’s, was fanatical about strawberry shortcake. If I conjure the foods of my childhood for which my father was responsible, three things come to mind: large, steaming bowls of cream of wheat with lots of cream and butter (that’s what we called margarine then), that universal dad specialty, “breakfast for dinner,” sometimes scrambled eggs with cheese, sometimes waffles, with lots of butter, and strawberry shortcake. My mom made it for him regularly. Sometimes we kids made it for him. But he also made it for us. His shortcakes, like his waffles, were mixed up quickly from a box of Bisquick with milk and oil. He made them extra large and smothered them with Cool Whip, sliced strawberries in sugar and butter. They always felt celebratory and were utterly delicious.

Kimmerer’s hunt for perfectly ripe wild strawberries to top her dad’s birthday shortcake was a kind of initiation into the gift economy she writes about so beautifully in the essay. It was, she tells us, “the wild strawberries, beneath dewy leaves on an almost-summer morning who gave [her] her sense of the world, [her] place in it.” She was raised by wild strawberries growing according to their self-possesed logic of season in patch and field. I was raised on genetically modified frankenberries, nearly big as my childish fist, available year-round and ensconced in sharp plastic cartons.

My experiences with strawberries have broadened though, and so my relationship with them has deepened. I have not lain in fragrant fields of wild hearts, but strawberry season in Wisconsin was a revelation and turning point in my understanding both of the fruit and of the gift economy the berries teach us. The summer I volunteered on a farm I’d bring home pints of tiny rubies that were so far from the red styrofoam fists that I gasped. They stained my fingertips and lips as I devoured them, amazed at their bright red intensity. The strawberry awakening was my entry into preserving. It was the Wisconsin strawberries that instilled in me an understanding of jam making as a way of paying the gift forward into community and time. I bought flats of the jewels each season from then on to capture in jars: strawberry paired with rosewater, rhubarb, dry rosé, or just on their own–perfect for the best PB&J you ever had. I loved gifting those stained-glass jars of early summer.

I understand her logic when Kimmerer suggests that by establishing a “feeling bond” between two people wild strawberries fit the definition of a gift– in a way that grocery store berries do not. One of the reasons baking and preserving are such essential practices for me is their ability to reroute the foods that we all consume back into the gift economy. The pleasure is in the transmutation. Time, care, and attendance can convert commodity berries back into enlivened expressions of gratitude and the fundamental joy of mutual acknowledgment.

And so it was with the graduation cake. I remembered a strawberry lemon something or other among Christina Tosi’s Milkbar style cakes and found the cookbook in the stacks. I quick cooked my last scant pint of sweet little local strawberries in with store-bought jam and layered them between strata of lemon-soaked butter cake, milk crumbs, lemon cheesecake, a rosy pink buttercream and the last of my stash of hot pink, extra-long homemade sprinkles. Happy niece got her strawberry cake. Happy Aunt understood the assignment, came in under deadline, and got to acknowledge how proud she was.

***

A couple of Sundays ago, my husband and I went to a gathering hosted by new friends. This gathering was called a salon and all were invited to speak, read, dance or otherwise respond to the theme of good neighbor. We were also asked to bring a dish–those with the last initial O. were among those who were to bring a dessert.

In 2020, just prior to moving to Georgia, I had written a short piece for edible Madison about just this topic. In it, I fondly remembered a very good neighbor and the ways food served as sign and symbol of our “feeling bond” of mutuality, growing intimacy and trust. I included a basic but endlessly variable butter cookie recipe and encouraged people to bake and gift the cookies as an excuse to get to know their neighbors better. The piece came to mind, I printed it up for salon sharing and checked this off my interminable do-to list. When the time came, I stumbled through the reading but was fortunate to have followed a man who spoke with passion and intelligence about the role of cookies and poetry in the politically-essential practice of being good neighbors to one another. He gave me much to riff on.

I realized later that I should have told the story of how my husband had mistakenly relayed the gathering as happening a week earlier, just a couple of days after my niece’s graduation. The story of how, after bemoaning the stress and lack of prep time and begrudgingly accepting that we’d likely end up bringing Dunkin’ Donuts or Oreos to this thing, how I decided to just dig deep and bake a double batch of the strawberry lemon cake. A large for the niece, and a smaller one with a more grown up flavor story, for the new neighbors. I splashed white wine vinegar in the jam for this one to mimic the pickled strawberry in the original recipe and I baked fistfuls of fresh thyme into the milk crumbs.That baking night had been long and effortful, but the cakes, finally left to set in the freezer ahead of their celebrations, were beautiful.

I can’t lie on Substack. I was not happy the day or two later when I learned the actual date of the neighbor salon. But I didn’t wallow. I hadn’t seen a dear friend whose father had passed since the funeral a couple of months earlier. She didn’t live far from me but man, had I been “busy.” I came to my sense. I set down whatever faux-important task was at hand. I wrapped that good neighbor cake up and decided it was time to be one. It felt great to visit with my friend. To presence each other. To slow each other down. To laugh and share something sweet. The cake economy. Sweet subset of the gift one. Reminding us, like Kimmerer notes, that “the more something is shared, the greater its value becomes.” Time, presence, laughter, goodwill.

The guy that spoke before me at the salon (to which we ended up bringing perfectly serviceable Farmer’s Market tarts) was named John. He shared a couple of stories. One was about standing on the porch of his house and asking anyone of his potential neighbors who walked by if he could read them a poem. The other was about baking dozens of cookies for neighbors standing in long election lines waiting to vote. Both stories reflected Kimmerer’s sentiment. The point is not necessarily the gift itself but the feeling bond it enables, the “ongoing relationship.” Gift giving enacts our connection and serves as a practice through which we might joyfully remember the stakes of that connection.

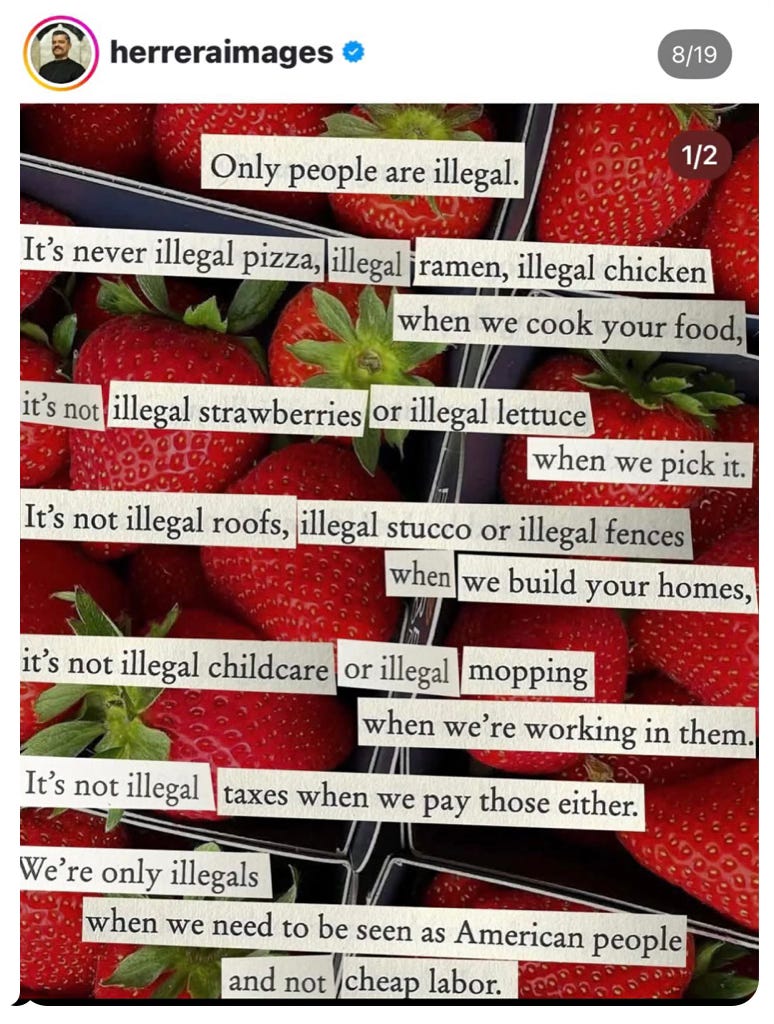

The cookies, the cakes, even the poems are practice. The socks we knit, the dog sitting, the jars of jam. We practice staying in connection to remember who we are and for times like these when stakes are high. Our neighbors are getting kidnapped, stolen away and bussed off to detention centers. This government is threatened by our connection. Sending out the National Guard in the hopes of scaring us into forgetting our ongoing relationship. But we’ve been practicing, right?

Look. Its simple. Bake cakes. Read poems. And Fuck ICE.

xx

Who or what has taught you something important about the beauty and urgent message of the gift economy lately? How are you committing to ongoingness in your relationships with your neighbors?

I always appreciate your takes on things and this one feels particularly life-giving. Getting ready to march this weekend and now I want to bring something heartfelt to give to my fellow protestors, just to reinforce how much we are all in this together. Thank you for the loving inspiration!

We received the most unexpected gift from a dinner guest recently: she brought a frozen log of compound butter, wrapped in parchment and tied with ribbons. RAMP BUTTER! It felt so intimate - how close and knowing of her to think, of course they’d appreciate this butter - and it was glorious, used to finish steaks and pork chops, slathered on sourdough toast for breakfast sandwiches, mashed with soft boiled eggs. Should I have been more adventurous with it? We’ll be visiting them for a porch dinner later this summer, and I’m thinking of taking a bottle of celery and cardamom syrup to mix with sparkling water, spiking optional.

86 47!