On Missing My Mom and the Black Repast*

Two things: first of all, thanks to those of you who’ve taken a moment to read, to share a comment, to email or message in response to these posts! You have no idea how our budding conversations around the rainbow Easter cake your talented son baked, how your pink magnolia is growing, hope, and even grief light me up! Keep them coming! And I promise I am going to work on learning how to be in more of a conversational mode on this platform too.

Secondly, Happy Mother’s Day! Whatever that means or brings up for you, I hope your spirit feels held in love and gratitude.

A version of the essay below was published in the magazine For the Culture, Issue 1: It’s Personal and the Pandemic 2021, edited by the incandescent Klancy Miller who now has a cookbook out by the same title.

***

Like all Black moms, mine, Jacky Woods, contained multitudes deep and honed. Consensus recognized her insatiable love of reading, acquisition of new crafting skills, and fierce loyalty in friendship among these, as well as a life-long commitment to education. She was everyone’s favorite teacher. Coming up, it seemed like she was always getting approached by former students. Kids who now towered over her 5’3” frame, would hug her with such enthusiasm: “Hey, Miz Woods! Hey, Miz Woods!” They’d thank her for this or that. Their cheeks would warm with blush as my mom complimented them, simultaneously piecing together which child this was, now “all grown.” Miz Woods was razor sharp, a big laugher, intolerant of nonsense or sentimentality. She was a fan of black and white Westerns and mediocre police procedurals.

Especially since taking a late-in-life professional pivot towards food, I think a lot about my mom’s food-related care work. She was a good and thoughtful cook and a decent baker, but entertaining was surely among her deepest talents. She knew how to make people feel welcome. She is why even though baking (and more recently writing) is how I express it, I understand my overarching project as one revolving around hospitality.

As, I think, for all Black moms, hospitality operated for mine in deep registers of care taking. Registers deeper than those that drive either the predictable reciprocity of dinner party logic or the transactionality of our hospitality industries.The cake or the curated dinner menu, the pot of beans on the back burner were in service. Not to say there wasn’t also deep satisfaction derived from learning a new skill, recipe, or technique. Or that we didn’t relish the aesthetic joy of setting a beautiful tablescape. It was just that her “why” always led beyond instrumentality with open arms towards community. The dishes we made were a tending to. My mother was exceptional but not unique. Her own practice had its trademarks, tells, and touches but the orientation was one shared with Black women everywhere.

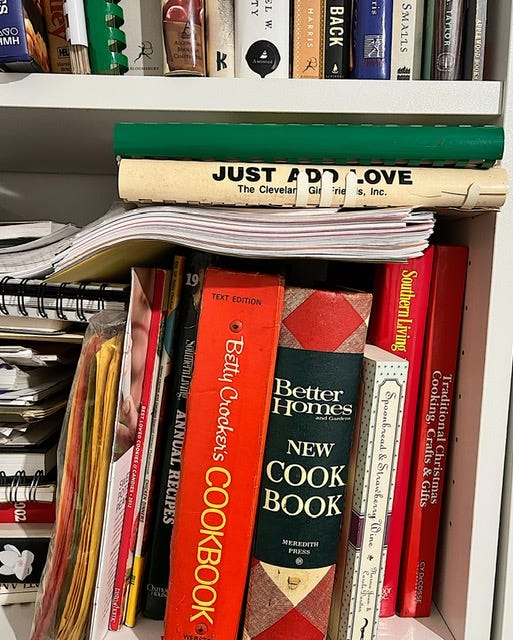

Around Christmas, for an upcoming birthday or house party, if a neighbor was ailing or had just moved in, mom and I would sit at the kitchen table and scan her cookbooks in search of the perfect projects or menu items. I loved the shared glow and expectation of this part of the process. Would this year’s gifts be jams or pulled candies? Which cookies would make Miss Carol’s hospital stay a bit more tolerable? Will this casserole freeze well? Mine was a working mom and a product of a certain time and suburb, so the most referenced volumes inevitably included Better Homes and Gardens, Betty Crocker, spiral bound church and club cookbooks, and Southern Living Annuals. When these failed to inspire, we turned to her tiny paperback copy of Spoonbread and Strawberry Wine.

Written by the Darden sisters, Norma Jean and Carole, this Black classic was one of my favorites then and still is. Surrounded by bucolic scenery and dressed in calico aprons and eyelet, the Dardens held baskets of garden-fresh produce for the cover shot. They affirmed a kind of direct connection to soil that intrigued my younger self. My dad had spoken of the farming in his past, but reluctantly. I had read Laura Ingalls Wilder and had white friends at school with grandparents who had farms (with horses!).

The Dardens though, pulled me gently by the hand into a frame of possibility that seemed somehow both more wild and more grounded than my own after school special-drenched, latch-key existence could fathom.

The cookbook, most recently re-issued in celebration of its 25th anniversary, takes its structure from the family tree. Recipes cohere around the relatives who favored them. My mom and I both loved the strong storytelling element and the way form followed and honored the sprawling path of Black family life. The celebrations, losses, grief, achievements, new births and so on were affirmative in their everyday-ness.Spoonbread helped me understand that each time mom and I made something in the spirit of tending to our families and communities, we were also planting seeds of tradition that would grow trees strong enough to weather storms.

My mom died April 8, 2020, after wrestling for eight years with breast cancer, in the midst of the COVID 19 global pandemic. At that time, before the coddled majority grew tired of protecting one another and stopped minding science and common sense, most states were allowing groups of no more than 10 to gather even for funerals, weddings and other major events. My husband and brother are among the immunocompromised in our family, so it seemed safest to hold a virtual service. We streamed from shuttered homes in separate states that which should have been experienced in the knowing intimacy of the collective. We sheltered, and grieved in place, instead of in each others arms and kitchens. No shift in circumstance would bring my mom back or make me miss her less but it took me a minute to understand why my grieving felt so stricken and ...well, sad.

Weeks later, going through her old cookbooks, I stopped to spend a while with Spoonbread. In addition to those organized around relatives, there are four chapters organized instead, around sites of hospitable sociality: Holiday Time with the Winner Sisters and New Years Day Dinner (both of which include complete, occasion-specific menus), On the Road, recipes received from friends met and visited while traveling , and a section titled, simply, Funerals, which suggests an assortment of cakes and pies to take to a bereaved family. As a cake baker, these are the recipes I sniff out first in any cookbook I pick up. That their placement in this book so thoughtfully reflects the logic of our sociality makes me love Spoonbread even more.

The remarks at the beginning of this section remind us that “The custom of caring for the bereaved goes back to ancient Africa where the family of the deceased was given not only food but items of value, including clothing and household items, by the entire community in an effort to offset the loss in a practical manner. In the antebellum South, churches, fraternal orders, and burial societies took over in a similar fashion and the tradition manifests today in our wake and repast traditions.”

The repast (or repass) typically, technically, describes the meal following a burial service. I think of the practice of the Black Repast more expansively and include food- related and food-adjacent care associated with practices around dropping in and vigil keeping as well as the actual post funeral reception. I think of the Black Repast as one element of what visual artist Kerry James Marshall would call a “counterarchive” to the transactional and hierarchical logic of mainstream hospitality.

Everything I know about processing grief suggests that it’s not the if (we will) or the when (each timeline is different) but the how of grieving that matters. For me and Mine, the best and healthiest grieving is accomplished in community. Writer Claudia Rankine has said that the condition of Black life is one of mourning. Grieving in the age of COVID and the context of Black Lives Matter brings what we already knew about the indivisibility of the personal and political into stiletto-sharp relief. The weight of the moment and the stark disparities it is revealing has distorted the contours and balance of my own fraught grieving process. Where a soft, bereft sadness may have led, I’m instead managing a white-hot rage. I am angry that, like too many of us during this public health fiasco, my mother died alone in hospital, visitors banned, instead of at home with her family bedside. I am angry that I couldn’t bake for her one last time; something that addressed that killer sweet tooth of hers. I am angry that her life—so full of laughter, placemaking, passion for teaching and learning, joy and love—had, by necessity and precaution, to be memorialized through the unworthy filter of Facebook Live. I am also managing mournful surprise as I realize the extent of loss and isolation I felt without the ability to engage in one of the most meaningful sites of Black hospitality —the repast.

From Spoonbread: “Friends and neighbors prepare and donate food to the grieving so they don’t have the burden of cooking for themselves or for the many guests who will be visiting. Those closest take up vigil to clean and prepare for visitors and receive the gifts of food.” Even for households in which a more formal protocol would normally take precedent, the Black Repast manifests in the spirit of visitation not invitation. My mom was a champion of the visitation ethos. She cultivated it wherever she found herself. Her neighborhood was close-knit and familiar due to her efforts and those of the other women in her community.

I have no way of knowing for certain, but I’d like to think that in a parallel world, one in which COVID remained dormant and uninterested in interspecies leaps, I would have been with my mom when she died. After the fact, I’d have stayed at her house in the lilac guest bedroom where I always stayed. She used to place little baskets of snacks, Nabs maybe, bottled water and prayer cards on the bedside stands for visitors. Now there are boxes of clothes stacked in the corner for Goodwill. Clothes her cancer- fighting body gradually grew too small for. I’d have felt her presence there and been able to bear witness with her bereaved husband. A wonderful spouse, he care took faithfully and patiently bore the sharp brunt of her projected frustration, fear, and fight. My brother and I would have helped him shuffle papers and organize. We’d find a photo or a note tucked away forgotten in a book, or smell her favorite J’Adore perfume still lingering on one of her sweaters. Maybe one of us would break down at these moments—the realization of loss taking our breath away anew. But we’d also hold space for each other. We’d keep those awful shows she watched on repeat during her long bed stays on in the background for comfort: Elementary, Monk, Wagon Train, Blue Bloods.

The dropping in would likely have begun before we felt entirely ready for it. It would have started as a trickle. A single neighbor: “Just wanted to check on y’all on my way out. You need anything from the store?” As word spread and at its height, a seeming steady stream of neighbors, friends and family members would be by to check in. Invariably, they’d bring food.

Spaghetti, ribs, someone’s suspect potato salad. Maybe just a greasy sack of Bojangles chicken biscuits. And of course the cakes. A neighbor’s poundcake, Fran’s famous coconut. We wouldn’t wonder where we’d get the energy to fix something. There would simply always be something out or close at hand when we only wanted a bite. The dishes (the cakes!) are central to but not the entirety of this hospitality. Someone would stay do the dishes, humming “When We All Get To Heaven” just under their breath. Someone else might wash and fold laundry. Errands would be run, couch pillows fluffed, the vase water changed and flower stems recut. Someone might think to gently place a blanket over the shoulders of my stepdad, asleep in his EZ chair. Those keeping vigil with you (often self-elected) make sure your home is welcoming and presentable for the next group of visitors but more importantly that it is a comfort and not a source of added stress for you.

I’m a devoted introvert. By now I’d be wishing for a few moments to just slump in a chair and stare vacantly, not having to talk to anyone. I’d be trying silently to will that one neighbor to stop wiping every counter surface after me and stop laughing at their own remembrances and to go sit down somewhere too. I know I’d be so grateful when the last went home and I had a moment’s peace with my own thoughts. But I would feel nourished, full, and taken care of. Held.

After the funeral would come the repast proper. Anthropologist Haile Eshe Cole, writes about the Black Repast in ways that resonate with familiarity and longing. At our repast, like hers, chocolate-skinned girls with “braids, plaits, and brightly colored hair bows” would run around the open boundaries of the dining hall, laughing in their Sunday best. Adults would be laughing too, smiling through tears, and catching up with each other. “How are things? Where is so and so?” “How old are the kids now?”And then, piled high on that “line of long rectangular white tables” was the food: fried chicken, macaroni and cheese, sweet potato pie and of course, the cakes. Cole notes: “In the space of the repast, the realities and inevitability of death, as well as the hope and determination to live, radically co-exist. It is also in this ritualized space where Black love is most pronounced.”

The Repast describes relational processes. Processes that Black Studies scholar Christina Sharpe would suggest occur in the register of the intramural, or among us. And the ordinary, everyday acts of hospitality the Repast makes space for cannot be reduced to the transactional. To borrow from Sharpe, it is through the process of the Black Repast (thought broadly) that we think about the dead and about our relation to them and to each other. It is ritual through which we enact grief, and what Toni Morrison called (re)memory. It is a space that might acknowledge the condition of Black life as one of mourning—but also one that recognizes mourning as a form of tactical acknowledgement itself. A method that Claudia Rankine reminds us has pushed movements forward from Civil Rights to Black Lives Matter. Within the space of the Black Repast, we acknowledge each other, we acknowledge that we are still here, and we acknowledge that it is the tending to that makes it so.

The Black Repast though, is more than mourning. It is also nourishment, support, shelter, and care taking in the ways of what I call deep hospitality. Black women, as the conveners, the space makers, the community caretakers, connectors, and, importantly, the preparers and servers of food are the carriers of this healing tradition.

I’ve seen the articles and memes that ask “What Do You Miss Most About Life Before COVID?” I miss my mom. Everyday. And because of physical distancing requirements, I didn’t even get a slice of Fran’s coconut cake. But in its absence I am reminded that the Black Repast is a path through the rubble. It models the kind of mutuality and simultaneous benefit that purely transactional models of hospitality inevitably fail to deliver. Scrambling industries might take a cue: solutions are often more about (re)membering and acknowledging than innovating.

***

Thanks as always for reading! How will you celebrate, love, mourn, sit in stillness, or carry on as usual this Mother’s Day? xx