The days are still stretching longer. It was closer to 8:00 than 7:00 by the time I got home but the sky’s slow softening into night was still in process and left me a little space to see what I might. I’ve been obsessed with expanding my knowledge of the songs and calls of my backyard birds since my naturalist group’s bird session last week, so I slipped out onto my back deck hoping to catch the last of the dusk chorus. The air held the day’s warmth and a gentle pre-rain humidity. I hummed a blessing over my tomato plants, nasturtium, fennel and the rest of my tiny kitchen garden. I sprayed eucalyptus oil in corners to discourage the ever-advancing ants, and then I stopped fidgeting and listened.

The distant white noise of rush hour traffic had died down, no planes rumbled overhead. The evening hush was a welcome surprise. Even the birds it seems had tucked in for the night. A chipping sparrow wrapped up her last thoughts and then, a lone, delicate descending call I didn’t recognize punctuated the quiet. I am quick on the draw with that Merlin app these days and I learned I was hearing a summer tanager. This was a new bird for me and I think one of our current migrators! I played the recording back later and had to laugh at myself when I heard the unself-consciously delighted coo I had made when matching this beauty to its call! Described as a “distinctive pit-ti-tuck” (although my guy added a creative waterfall of syllables to his version), I kept my eyes and ears trained towards the tanager’s call. A flicker of obscured movement high in a pine and then a flash of red, muted in the dying light, as he flew into the upper arms of my poplar.

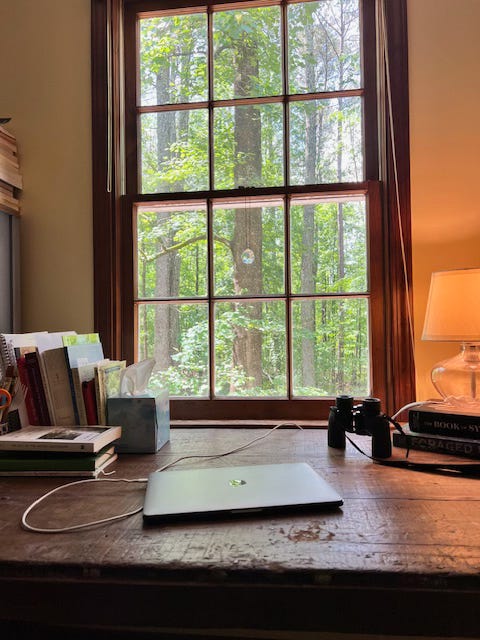

I love this yellow house on the high ridge and I am grateful to its builders for cradling the house in the arms of a giant white oak that marks the property line on the west side and a now-towering tulip poplar about 30 feet from our patio marking due south. The tulip poplar sits on a gentle rise in the center of our back lot and lucky for me, also situates in the near center of my writing desk window. Along with the deck below, this is a favorite still spot and I have spent many hours studying and admiring this tree.

This tulip poplar (tulip tree, whitewood, yellow poplar, Liriodendron tulipifera) is a linchpin of my back yard’s ecology and the tanager is only one of dozens of birds I have seen fly into its arms for shelter, rest, food, and a surveying view. This time of year, when so many migrators are moving through to breed, feed, and otherwise party, the scene is lively. This little patch of territory is shared among Northern Cardinal, Eastern Towhee, Bluejay, Tufted Titmouse, Robin, Warblers Pine and Parula, Black- and Yellow-throated, Red Eyed Vireo, the bird of mystery Cedar Waxwing, Bluebird, Eastern Phoebe, Finches House and Gold, Mourning Dove, Chipping Sparrow, Great Crested Flycatcher, Carolinians Chikadee and Wren, the Woodpeckers Tufted, Furry, Red-Bellied and Pileated, Crows, Hawks, Vultures, Owls, and…Summer Tanagers!. Some of these don’t frequent the poplar, it stands a bit apart from the wooded cover of our wild yard. Not enough cover for the hunters and the woodpeckers have learned they have little purchase with it’s sturdy midwood and move on quickly to the soft riddled guts of one of the surrounding pines. But for many of these birds, the poplar is a favorite. And all are welcomed with what seems to me a deep and joyful hospitality.

It rained hard and steady overnight and the spring greens that have been deepening and filling out these last weeks are saturated now. So are the rich browns and russets of bark and clay. Avocado, sea foam, dark emerald, lime and a thousand other shades of green comingle among the dogwood, hornbeam, hickory and beech that crowd the stories beneath towering loblollies. The sun moves from behind a cloud as I type and, catching a shift of the light’s movement I look up and out the window– the entire scene has transformed. Everything is lit from within. It’s an extraordinary show of light, shadow, soil, stick and chlorophyll. A morning breeze collaborates with the shifting light. A thousand patterns emerge and recede. Everything green and yellow and bright dances through the steady verticality of trunks. The tulip poplar as principal dancer is out before the corp, sparkling and vibrant. If I crane to look at the branches that just exceed the upper limits of the window frame, I’m met with an explosion of characteristic blooms: ostentatious, fluttery pods of creamsicle, limeade, and lemon drop all dripping silvery rainwater from their cups and petals.

My attention in the direction of the poplar has been rewarded lately with a number of hummingbird sightings and visitations, some lasting for several seconds. The other day a ruby-throated hovered at the office window long enough for me to gasp and take in the shimmering emerald perfection of her scaly little feathers. This morning I watched one at the screen door. She inspected my garden pots, buzzed to my left and then zipped upward. Before I start googling “spiritual meanings of hummingbird sightings” I remember that we are in the heart of tulip poplar flowering season. These magic birds are here, not to bestow me with spiritual blessings (indeed, every sighting is a blessing, they’re so fleet and gorgeous) but instead, at the invitation of the poplar who’s kool-aid-colored flowers produce copious, sweet nectar that restores the tiny birds after long migrations. These trees are the tallest of the temperate deciduous forest and their flowers produce among the highest nectar yield. I don’t care if it’s weird that I imagine the tree chanting to the hummingbirds “I love it when you call me Big Poplar” in Biggie’s voice.

When I moved back to Georgia towards the end of 2020, the tree brought to mind a different song, however. One that underscores the ways landscape, place, and the lived experience of this country’s history are always co-constitutive. The lyrics of Strange Fruit, one of Billie Holiday’s best known tunes, were written by Jewish activist Abel Meeropol. The song only solidified its status as “an important index of early Civil Rights activism in the cultural sphere” with Holiday’s informed and heart-aching interpretations from the floor of the Cafe Society nightclub in the late thirties and forties.1

Holiday’s working class blues pedigree, her participation in political activities, rallies and demonstrations, her songs about self-sustainance and capitalism (God Bless the Child) but especially her nightly performances of Strange Fruit put Billie Holiday at the cultural center of Civil rights and leftists politics during this time period. An anti-lynching anthem, the performances of the song brought the vivid and visceral horrors of Southern terrorism against Black people into New York’s intimate and integrated jazz spaces:

Southern trees bear a strange fruit Blood on the leaves and blood at the root Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees Pastoral scene of the gallant south The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh Then the sudden smell of burning flesh Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop Here is a strange and bitter crop

The tulip tree is not even a true poplar (this common name comes from the tulip-shaped leaves and flowers and the way it mirrors the tall, straight growth habit of the poplar), but it is a magnolia. And while it grows native across Southern Ontario, central and eastern U.S., it is associated for me, with the landscape of the South.

We would do well to remember, especially in this moment when our educational system, libraries and institutions of memory and record–our very language–are all under attack, that the landscape holds our memory too. The landscape is, of course, shaped by our history and it continues to bear compassionate witness alongside and with us. I’ve read in many places that trees mourn felled members of their community. I’ve written elsewhere about my own need to mourn with and be comforted by trees. Surely those poplars and magnolias of Holiday’s song cried out too, for the fruit they were forced to bear. Is it much of a stretch to imagine the arboreal community sending electrical signals of tree comfort and strength via mycorrhizal network to the fruit-bearing tree? Feeding it, sending nutrients, holding it up, just perhaps as they might another comrade beset by beetles or a pathogenic fungus.

When we moved back here and into this house in 2020, my mom had been dead not half a year and Ahmaud Arbery’s modern-day lynching had been committed shortly before that. I had designed grief cakes for both of them and wrote at the time, of the complicated relationship between Black bodies and the outdoors:

And the Black body still knows that some places are inhospitable. The Black body has learned the intimate connection [and shifting potentialities] between geography and well-being. The Black body is always—at least partially—out of time and out of place. Several weeks ago I watched a YouTube talk with Fred Moten and Saidiya Hartman theorizing the Black Outdoors. Moten noted that he can’t hike a trail without considering the ghosts of runaways. Hartman’s discussion of the petite marronage brought to mind for me the ‘leave no trace’ principles I learned as a young trail runner.

I don’t know how old “my” tulip poplar is, but you can understand why, back then, I asked it questions it couldn’t answer. Questions about what its kith and kin saw and knew about this territory so lush and hostile. One response, perhaps the only viable response, has been to commit, as I have in these years since, to learning the territory, to attending to my homeplace and to getting to know “my” poplar. To invest myself in this land, that it might reflect back to me fundamental aspects of my story and truth. Lauret Savoy quotes Keith Basso of Wisdom Sits in Places fame in her essay Confronting the Names on this Land: Place-making is both a way of ‘doing human history’...as well as ‘a way of constructing social traditions and, in the process, personal and social identities. We are, in a sense, the place-worlds we imagine.”

This poplar that I have studied most days these last four and a half years, resisted my initial urge to see it only within the historical frame of the Strange Fruit lyrics, only as reference point. It invited me not only to remember, but to imagine—and therefore see—more life. Like me and all other living beings, this poplar is whole and continually becoming. It continues to patiently teach me how to see its fullness and subtleties. Big Poplar is steady and generous with deeply furrowed, moss-mottled bark. Big Poplar dances, beckons, comforts and hosts, shelters or feeds lichen, birds, squirrels, deer, bees and fungi. Big Poplar moves through seasons of loss with enviable dignity and seasons of blossoming with grace and humility. Likes, dislikes, collaborators: Tulip poplars like deep and moist but well-drained soil, especially in valleys on slopes (like the one “mine” is on) and to be near creeks or streams. I recently participated in a cool workshop in which we learned how to forage morels. Turns out this fungal delicacy is associated with tulip poplars and likes to sprout up along their drip line. Of all Atlanta’s Champion Trees, fifteen are tulip trees. The girth of these champions ranges from 171 - 235 inches. “Mine” measures in at 135 inches around and if I had to guess, is between 80-100 feet tall. It won’t make the record books, however, Big Poplar is a champion to me and all the other critters that depend on it. As long as I’m in this yellow house on the high ridge, staring southward off my back deck, we will continue to heal and become together, placemaking collaborators.

Who’s teaching you how to grow? What stories do you keep? How do you tend, water, and augment them? xx

Hairston (O’Connell) , M. (2009) The Wrong Place for the Right People? Cafe Society, Jazz and Gender, 1938-47. Doctoral Dissertation, New York University.

There's a tree I visit in the Cherokee Marsh I frequent that eludes me but we have a relationship. I can't go long without hugging this tree(s) because their appearance mirrors how I feel. The outer tree is actually dead and hollow, looks as if was struck by lightning at some point. Up and through the dead and hollow bark rises another tree the bark barely visible until 30-40ft up. I'm unable to really see clearly what type of tree it is. I hug the base and tell her that I love her and that we'll grow together. This tree feels like a demonstration of intergenerational power this country has stifled since it's inception. Our encounters are a reminder that even when I can't see clearly there is always evidence, guidance from the land that holds us. Thank you for this beautiful tribute to your poplar friend💞